When I was a kid, issues with bullying, poor teaching, and undiagnosed depression and anxiety led my parents to move me around to different schools with some frequency. Midway through my freshman year of college, my father died unexpectedly, leading to enormous financial strain that meant I had to leave my out of state college (where I was frankly miserable anyway. Have you ever spent a winter in Olympia, Washington? Everyone has damp socks all the time.). All together, I attended two different elementary schools, one junior high, two high schools, three colleges, and two graduate programs.

Social stability was impossible. I’d make a few friends at one school (or more likely, get beat up at one school), then find myself in a new school with already established social cliques. Also, maybe this is just growing up in an urban environment during the socially and economically tumultuous 70s and 80s, but girls were awful — nasty, mean, physically abusive — and boys were worse. Because I had big boobs, boys wanted to touch me, but not in ways I understood, so they chased me around screaming insults until I cried, and then they laughed at me for crying. Academically, I was shuffled off into the GATE program for “gifted and talented” kids, which only meant more bullying, insults, and harassment. This is not a pity party; it’s the reality of adolescence for any kid who’s weird, smart, neurodivergent, queer, or just different. You get singled out, and it’s lonely.

At some point I just gave up and figured I was cursed to be friendless. By high school I had a small posse of outsider-y smart female friends, one friend I made at Shakespeare summer camp (where everyone was so deeply, unfashionably nerdy that I was truly happy for what might have been the first time in my life), who I’m still friends with today. In college, as a commuter student at a small liberal arts school where everyone lived on campus, nobody even knew who I was except for the professors who found me startling: why, they’d ask, was I at this frankly mediocre school and not somewhere better? (couldn’t afford it, didn’t have the grades.) My friends were punks and hip hop kids who lived in squats and went to state colleges and junior college and art school, not the wealthy, drunk kids who slept through classes and spent their weekends watching sports and participating in sexual assaults, which the school was constantly covering up. I was, in other words, unpopular. In grad school I clung to the one gay guy who said he liked my shoes at orientation and we passed notes and rolled our eyes at one another during workshop. And the other students went out and drank gallons of beer together and talked shit about us. Everything was a clique.

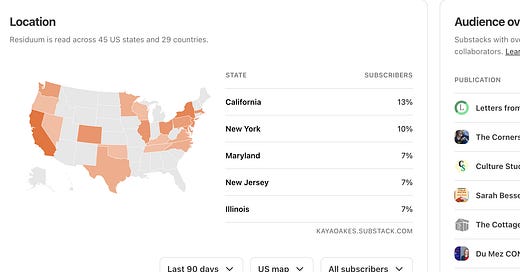

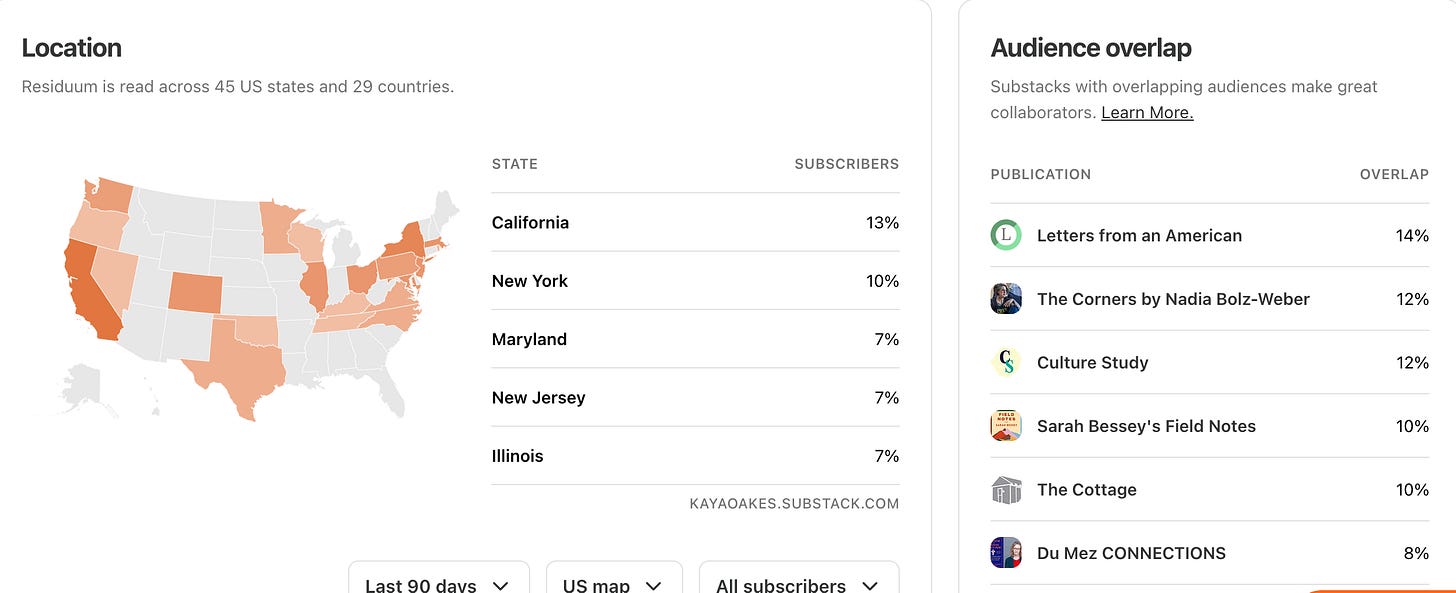

My Substack is like these Substacks except that these Substacks have tens of thousands of readers. These are the popular kids. Also shout out to my Californians!

My years of education were a preview of the literary life. To this day I can tell right away if a writer was the kind of kid who was popular or if they were not. The writers who were popular kids have a lot of self-confidence. They were the early adopters of Instagram, where they post a lot of selfies (popular kids, of course, were always also attractive kids and my round potato face, bad teeth, cystic acne, uncontrollable hair and chunky but also unusually tall body followed me into adulthood). They’re the kind of people who got those early Substack deals that added up to hundreds of thousands of dollars, they have podcasts, they love conferences and will constantly remind you how conferences are the best time of the year!!!, their psych meds are well managed, they even dabble in spon con. If you remember the kerfuffle over the article about the Bad Art Friend, an article about writers being shitty to one another, the thing that stuck out the most to me was the fact that there are literary cliques even among people who write best-sellers. The popular kids eat one another and spit out the bones.

The unpopular kids have Substacks that never seem to break 1000 followers (ahem), they hate Instagram because everyone on Instagram is a popular kid, unpopular kids were good at Twitter because they’re good at snark, they suspect that the popular writers only read books by other popular writers (likely true). The unpopular kids see Substack handing out checkmarks to the popular kids and sigh. They see the popular kids in The New Yorker and the New York Times because the popular kids are friends with other popular kids who become editors at those kinds of publications, and the unpopular kids’ friends are editors at niche little magazines which publish great writing but which, you know, nobody reads. The popular kids get Big 5 book deals and go on book tours; the unpopular kids are published by indie presses and have to beg the local bookstore to stock their books.

Sometimes when I see people with bumper stickers showing off where they went to college it makes me a little bit sad, because that means those people peaked in college. Same for people who attend every high school reunion. If those were the best years of your life, what do the rest of their years feel like? One thing about being disappointed by other people as a child is that it prepares you for being disappointed by people as an adult. If you were alone a lot, you learned how to be alone, which, as it turns out, is a pretty useful life skill for writers.

Writers who thrive on audience and attention must suspect that you can lose both of those things in a heartbeat, especially in these days when media, even social media, is collapsing all around us. Writers who can keep going when the spotlight isn’t on them, on the other hand, can survive losing agents, editors, book contracts and audiences. As the publication date of my next book approaches, I’m not worried about how many people will read it (okay yes a little bit, I’m human after all) but I am hoping the right people will read it: the people who will find it helpful, hopeful, the people who need its central message, the people who might share it with someone else, mark it up, bend back corners, make notes. I’m not going to have the kind of career where I make the New York Times best seller list and put that in my bio and remind people of it with some constancy. I have and will have the kind of career where I get an email once in a while from a person who says your book moved me, your book mattered, and I’m not going to have people lining up to meet me at conferences, and I’m not going to be on Colbert (even though I suspect he’d actually like me), but I’m going to have people who care for me and love me and know me deeply. And that, to me, is actual success.