There’s a thing men do to women, particularly when those women are younger, and that is to tease. It’s a way of putting us in our place, perhaps, or a way of coping with the idea that we might actually be more intelligent than they’d initially suspected. This started when I was a child, maybe eleven or twelve. My father and I had gotten last minute tickets to see Troilus and Cressida at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. The director decided to amp up the homoerotic tensions in the script, as this was around the time scholars were finally admitting that Shakespeare himself was writing from the point of view of a man attracted to other men, when the world was awakening to how queer everything could be.

When we got home, a family friend came over and I told him that Achilles and Patroclus were definitely gay. He sputtered and said I couldn’t possibly know that, the Greeks just had close male friendships. It started as a joke – hah hah, this kid thinks she understands Shakespeare – but when I demonstrated some understanding of the textual evidence by hauling out a marked up copy of the play (I was, so, so deeply lonely as a child), the tone changed. Teasing can swerve into humiliation. And who is more easily humiliated than a young girl?

Patroclus: A woman impudent and mannish grown

Is not more loathed than an effeminate man

In time of action. I stand condemn'd for this;

They think my little stomach to the war

And your great love to me restrains you thus:

Sweet, rouse yourself; and the weak wanton Cupid

Shall from your neck unloose his amorous fold,

And, like a dew-drop from the lion's mane,

Be shook to air.

Troilus and Cressida, Act IV, Scene 5

It is hard, now, to look at my cancer-scarred body and remember that when I was young, a certain type of man consistently pursued me. I was tall and thin, with big sad eyes, and I was absolutely desperate to be a writer, the picture perfect notion of a potential literary groupie. Older men, men who liked to tease, literary men. They seemed to materialize wherever I went. I worked in a bookstore and authors came through for readings, I was in grad school and authors came to guest teach, and many of them looked me up and down, touched my arms and hips and shoulders, whispered to me, teased me. Rarely did I have much interest. I didn’t like old men, men with ex wives and daughters my age and mortgages. I wanted something more dangerous. I wanted something impossible.

My type was musicians, the more drug addicted, alcoholic, and ill tempered, the better. I’ve had enough therapy now to understand that my alcoholic father’s early death set me up to try and be the savior of men. I used to play this verse from Bob Dylan repeatedly when I was writing bad poetry in grad school and swooning after guys in bands. It was beautiful. It set me up for disaster.

Suddenly I turned around and she was standin' there

With silver bracelets on her wrists and flowers in her hair

She walked up to me so gracefully and took my crown of thorns

Come in, she said

I'll give ya shelter from the storm.

J was tall with a corona of prematurely white hair, but also young and vigorous, and I was in between breakups with various guys in bands when we met. I knew who he was when he sauntered into the bookstore – my poetry teacher and he were in the middle of some kind of complicated, inappropriate thing since she was married to someone else and much older, and he’d just won the kind of big poetry prize only poetry people care about, but they care about it a lot – but while he was a writer he also loved music and fiddled around on a guitar playing pop songs and wrote about music for magazines.

He teased me, all the time, teased me enough to get me over to his apartment where there were various objects left behind by other women, where the phone rang and women called him, where he corresponded with lots of different women about writing and music and politics and art. He was already famous in our little literary world, but he didn’t have a car, so he’d borrow mine, and always toss whatever cassette I was listening to into the backseat and turn the radio to some dreadful pop station. Pop music made him happy. He’d play this Oasis song about a girl in a dirty shirt and I’d sit there thinking with some desperation, is this for me? Is any of this for me? I was allowed to go with him to readings, maybe as ornamentation, because I could dress well and look presentable and speak articulately and I had a car. I met his friends, older and smarter, and went with him to parties where people talked about Marx and auteur theory and drank white wine. My own preference for red wine was mostly because I knew where to find the cheap bottles on the bottom shelf that wouldn’t make me throw up.

He teased me, all the time, and sometimes didn’t return calls, and sometimes didn’t return emails, and went off to Paris and New York and came back and would turn up again, and things would stop and start, stop and start. I wanted so desperately to be a writer and he was ascending the literary ladder with a kind of violent speed – lured by different schools with offers of professorships, pursued by literary magazines, and sometimes he needed a girl with big sad eyes who understood music and literature, and it was me for a while, but soon after it was a grad student, then someone else and someone else and someone else.

But he did tell me, more than once, that I already was a writer. Told me to stop calling my colleagues “professor” when I started to teach. Told me that someday, “they” would seek me out, “they” meaning the literary establishment, which sort of happened and sort of did not. Like a good Marxist he hated religion and once told me about being at a party where the professors and literary critics and writers toasted “to the death of the pope,” so my religious bent was something he would have mercilessly made fun of me for. We kept crossing paths, for years and years, for this is a small place pretending to be big, and when he wasn’t in Paris or NYC or Iowa City, he was often in Berkeley. And he’d always tease me, but eventually I just laughed it off. I met someone else when we were spiraling out of whatever it is we were doing and that person is sleeping in this morning. That’s the person who sat with me during chemo and has gone to my own readings and literary events for nearly three decades. He too is a musician, but he doesn’t tease women. Not often, anyway. But he is absolutely not a writer. I made sure of that.

Another friend texted me a couple of weeks ago and said that J was dead in his early sixties, and then I heard from other friends who knew him. We had stopped running into one another, which I thought was a bit strange, but then again, I was floored for a year by cancer and had stopped going to most literary and academic conferences years before that, finding them tedious and claustrophobic. But if his name was in a program on a panel I’d step in and stand at the back and see him, handsome and difficult, abrasive and funny, and we’d smile at one another.

The bookstore where I worked is gone. And now J is gone too, the men of my youth slowly falling victim to disease and bad habits and accidents and time. I don’t know if he loved me, but he cared for me and wanted me to succeed. The teasing was reflexive, I think. It was a way of keeping me and my big, unwieldy writerly feelings at arm’s distance. That was ultimately for the best. I’ve dreamed of him a lot in the last few days, though – the half smile, the bad teeth, the snark, the laughter, and yes, even the teasing. We weren’t meant to last. Not much is. But we were meant to orbit one another, sometimes at a distance, and sometimes up close. Now it is just me and all others in his orbit, remembering.

Then the conceit of this inconstant stay

Sets you most rich in youth before my sight,

Where wasteful Time debateth with Decay

To change your day of youth to sullied night;

And all in war with Time for love of you,

As he takes from you, I engraft you new.

Shakespeare, Sonnet 15

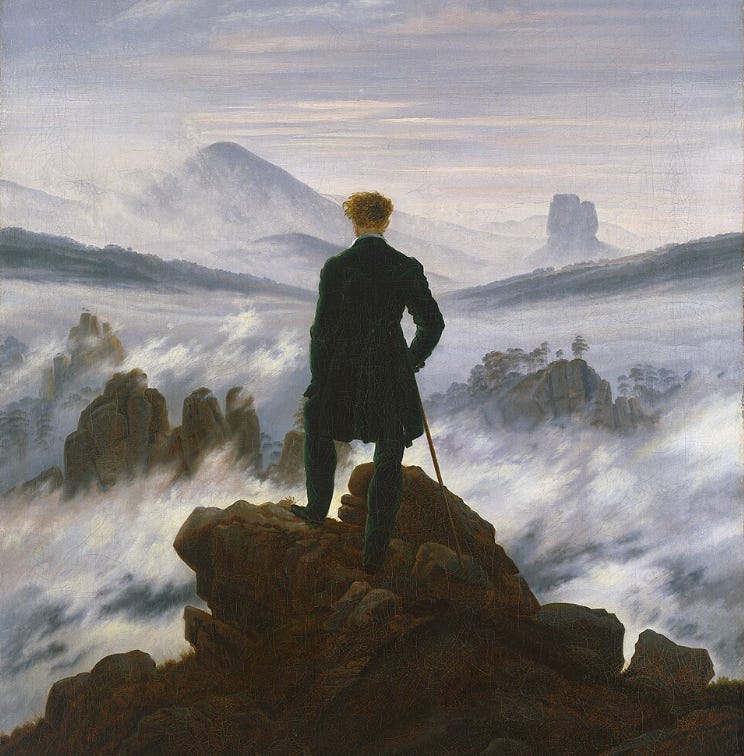

Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, Casper David Friedrich, 1818.