The ok boomer thing is fascinating to me (and I love that it already has such an in-depth Wikipedia entry). I work with Gen Z and young Millennial students every day, and suspect they think I may be a boomer (guys, I am sorry to disappoint you, but I am not). They definitely think the admins at the university are boomers (correct). They know everyone running for president is a boomer (which is actually not true —Kamala Harris and Julian Castro are Gen X, as was Beto O’Rourke; Mayor Pete is, of course, a Millennial, but the power candidates are, of course, all Boomers, because that’s who we elect in America).

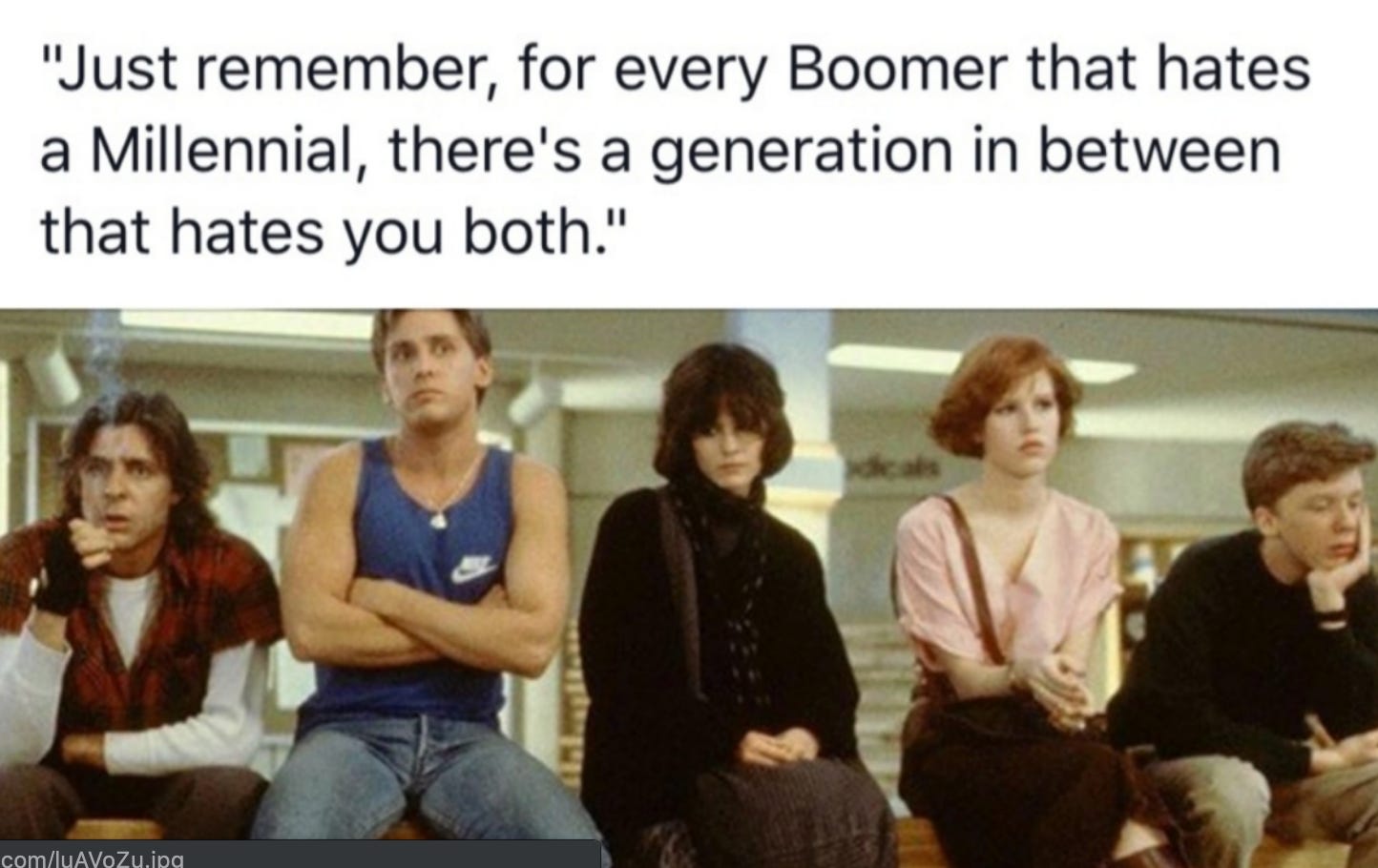

The memes people keep sending me on Twitter are the ones about Gen X being left out of this debate. They are funny — cynically so, but funny, because all of them emphasize that Gen Xers are left out, forgotten, erased. And in a lot of ways, we always have been. There was a brief cultural moment around the time I finished college in the early to mid 90s that people cared about Gen X. But even in the name they gave us, there was a negation and an erasure that never sat easily with a generation raised in the shadow of global nuclear war and decreasing job security.

There was a day a few years after I began teaching at Berkeley when a nationally-renowned Boomer economist told me and a few other Gen X faculty (none of us hired on the tenure-track and all of us adjuncts or lecturers, by the way) that our Millennial students would be the first Californians to have less than their parents did. That they’d be less likely to own homes, graduate without debt, and find job stability. None of us owned homes (still don’t!). We all had piles of student loans. And I’m the only one still teaching. In my gentrified neighborhood in Oakland, it’s Millennials who are buying multi-million dollar flipped houses and driving Teslas and drinking Kombucha on tap. It’s Lululemon-clad Millennial moms pushing baby strollers (or, frankly, nannies of color doing the pushing). The tech world likes to say it’s about disruption, so maybe that’s a kind of disruption, too. Millennials don’t have the same stability as their Boomer parents, but some of them do have money. Lots of it. So do some Gen Xers: the CEOs of a lot of those tech companies are Gen X.

The truth is that generational theory is bullshit. It’s so deeply bullshitty that among its biggest advocates is Steve Bannon (ok boomer). I was offended when the very successful Millennial writer Emily Gould went on a Twitter rant about “okay Xer,” claiming that we took all the tenure-track creative writing jobs, bought the last cheap urban houses with our 90s dot com salaries, and ruled the New York media landscape. I was offended until I realized she was talking about white Gen X men. In New York. In the media landscape. Which I’m not a part of and never have been. So that’s not “okay Xer.” That’s “okay powerful white media guy in New York.” We all have our extremely specific petty grievances (ask me about Bishop Barron sometime).

We’re probably going to elect a powerful white guy yet again, and he’ll definitely be a Boomer, so, to quote the Gen Xer Sinead O’Connor when she tore up a picture of the pope on Saturday Night Live to protest clergy sexual abuse (and though she was reviled for it at the time, she turned out to be pretty prescient about that pope’s enabling of the cover-up culture in the church), maybe we need to stop squabbling and “fight the real enemy.”

I Skyped into a class at Fordham earlier this week to talk about my book on why Gen Xers, Milennials and Zers are less religious than any previous generation, and the ok boomer thing came up because one thing anyone who’s not a Boomer share in common is a suspicion and distrust of institutions. Why put your faith in old white guys? Really, why? I know a lot of lovely old white guys who are willing to step back and let others take the mic on occasion. I also know a lot of craven, greedy, abusive, resentful old white guys. On the other hand, I spoke to a group of Boomer Catholics last week and they peppered me with questions about how to get Millennials and Gen Zers into church, and when I asked them if they realized that Gen Xers had mostly stopped going too, they were nonplussed. This is why I feel a lot of solidarity with Millennials and Zoomers (or Zers or please, choose a moniker you like before we give you one you hate) and why even with my Boomer friends, some of whom I deeply love, I struggle to find it fair that they own homes and have comfortable retirements after similar careers to mine, when those things still elude me as I stare down my fifties.

Then again, I see homeless Boomers on the streets of Oakland, and I work with non-tenured Boomers at Berkeley who are in the same economic straits as me. I’m a middle child, and the age gap between me and my three older siblings is so big that they are Boomers and I’m an Xer, and my younger sister is so much younger than me that she’s an Xennial (spare a thought for our poor mom). We could enact our own family version of the generational wars, but we’ve settled instead on helping one another out as much as we can. It’s far too optimistic to believe that previous generations who pulled the ladder up after themselves in their climb to success would be able to change en masse, but what if we chose instead to find solidarity in our shared struggles, in the ways we’ve been marginalized, in our erasures and resentments against those in power who cling to power rather than sharing it? If people stoped shunting one another aside because of perceived differences and focused instead on common ground, what would that America look like? It’s all impossible because of capitalism, of course, but in my idle moments as an invisible, erased Gen Xer, I do wonder.

But, you know, the memes would suck.

This is the first edition of my re-birthed newsletter and while I cannot promise it’ll arrive with any regularity, I do hope it can be a place to explore these questions I often write about: marginalization, faith, equality, a more just society, aging and feminism. The in-between states, the things that happen outside of the mainstream and off the radar of the mainstream media — those are the things that are the most fertile ground for me as a writer. So thanks for joining me here.